Language is humanity’s killer app. We are the only species that can communicate complex ideas and also pass them through generations. It’s often said that our ability to communicate in a such a manner has put us atop of the food chain. Big technology firms have become so powerful because they’ve put a metaphorical fence around all that we say, and therefore, control all that we know. Big tech as we’ve come to know them are basically, in the language business.

While it’s clear that our voices all all unique. What is less known is what can be gleaned from them

The Verbal Reveal

Despite our hearing abilities being inferior to many other animals, we humans can deduce a surprising amount of information from listening to each other speak. We can make pretty good guesses at someone’s gender, age and perhaps even levels of education.

However, machines can infer far more than a human ever could from a voice. In the developing branch of Artificial Intelligence which focuses on speech, much has been achieved, even in the early days of understanding sentences and how to respond. Known as Natural Language Processing (NLP), this field of A.I. can discern with significant accuracy someone’s age, gender, ethnicity, education levels, socioeconomic status, and even uncover health conditions.

What we tend to forget is that the voice recognition system is doing more than just listening to words. It is also cross-referencing what has been said with other information that can be extracted from the device (smartphone / internet browser) delivering the voice data.

In essence, NLP does what humans do. When we meet with someone, we look at our surrounds to provide clues on how to navigate the conversation. We look at what people are wearing and the venue we are in – everything visual and contextual that might support the verbal interaction. Conversation that comes with context nearly always has better outcomes.

This is part of the reason telephone customer service lines are so often a poor end-user experience. When an NLP engine interacts with enough voices for long enough, it can create new forms of pattern recognition. Sourced from vast data sets incorporating 65 per cent of the world’s population, NLP can match data points to voice prints far beyond what any human ever could. What NLP may uncover is almost limitless.

The Mirror of the Brain

Using our voices is not as simple as it seems. When we speak, a complex process is launched, activating both physical and mental faculties. Involving the lungs, voice box, throat, nose, mouth, lips, sinus and jaw shape. Using your voice activates more than 100 muscles every time it is used. Additionally, your voice is the reflector of the brain – what it knows, believes and how it responds to audio stimuli. As the MIT Media Lab voice researcher Rébecca Kleinberger says: “The voice is very much the brain.”

Voice to Face

A single voice can now reveal unfathomable volumes of information to an A.I. engine. Researchers have even been able to generate images of faces based on information ascertained from individuals’ voice data. I know – this blew my mind too.

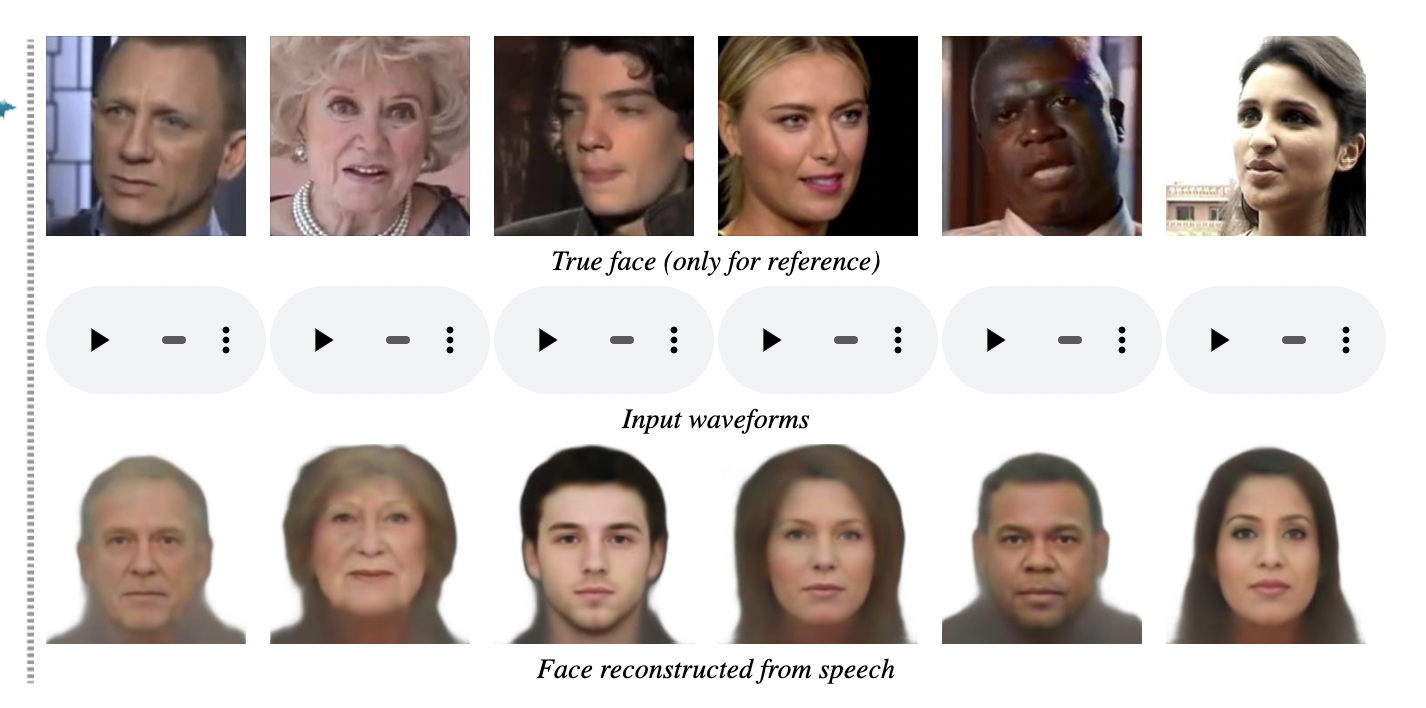

A 2019 Cornell University research study was able to reconstruct facial images of people using short audio recordings of their speech. The facial image reconstruction was produced through training a deep neural network, utilising millions of YouTube videos of people conversing naturally and without a script.

The network training methodology looked for correlations and co-occurrences of faces and voices. It matched the probability of voice patterns with pixel patterns to guess what an unknown person’s face might look like. The results below are quite astounding, given how nascent this technology is.

BONUS – Follow me on TikTok for daily motivational sound bites of goodness. No dancing from me – I promise.

Everlasting Conversations

At Amazon’s recent re:MARS conference for Machine Learning, Automation, Robotics and Space, a new Alexa feature was thrillingly unveiled. Amazon’s AI assistant can now impersonate voices of users’ dead relatives. The demonstration featured a child asking his deceased grandmother to read out a bedtime story, whereupon her voice obligingly pours out of a nearby speaker. As you can imagine, this feature was met with both admiration and outrage. Many called it plain creepy.

While we might think that it would take a deep longitudinal data set for Alexa to learn how to mimic a real human voice, Amazon claims that its AI system can learn to imitate a voice from less than a minute of recorded audio. Given how prevalent recordings of people are now on both video and audio, it wouldn’t be difficult to create a voice clone of a loved one. Or pretty much anyone who has ever been on the internet.

While Amazon hasn’t given an indication whether this feature will be rolled out, the technology will surely leak across the web, as it always does. The website Fakeyou.com is a veritable “Choose Your Own Adventure” of actors, celebrities, singers, cartoon characters and public figures whose voices can be manipulated to say whatever you desire. It’s possible to upload your own voice and even clone that.

The opportunities bubbling out of this are intriguing. When we have to make that dreaded phone call to the bank or tax department, we may be able to choose from Scarlett Johansen or Ryan Gosling as our customer services operator to make solving the issue a little more pleasant. If we combine already existing music AI systems with voice cloning we may be able to create new Beatles tunes – John Lennon may sing again. Animated voice actors for long-running animations like The Simpsons may well be delivered a pink slip. Radio hosts from years gone by could join the podcast bandwagon to cater to more senior audiences.

The Voice Cloning Industry

Voice is the latest in a long line of emergent cloning marketplaces. This creates new value, revenue sources, investment and of course, potential legal conflict. The voice and speech recognition industry (I’m calling it ‘Big Voice’ — you heard it here first) is estimated to exceed $US20 billion by 2026.

If we thought it was already difficult to distinguish between what is real and what is fake on the internet, it’s only going to get a lot more challenging.

—

Keep Thinking,

Steve.