Last week I was invited by TED to lead their live Circles event discussion. The topic was Nationalism versus Globalisation. As preparation, all participants had viewed this TED talk on how nationalism and globalisation can co-exist. I then led a discussion to take a deeper look at the subject, in the context of a post-COVID-19 world.

These are my conclusions, which I think provide a solid template for examining the global economy:

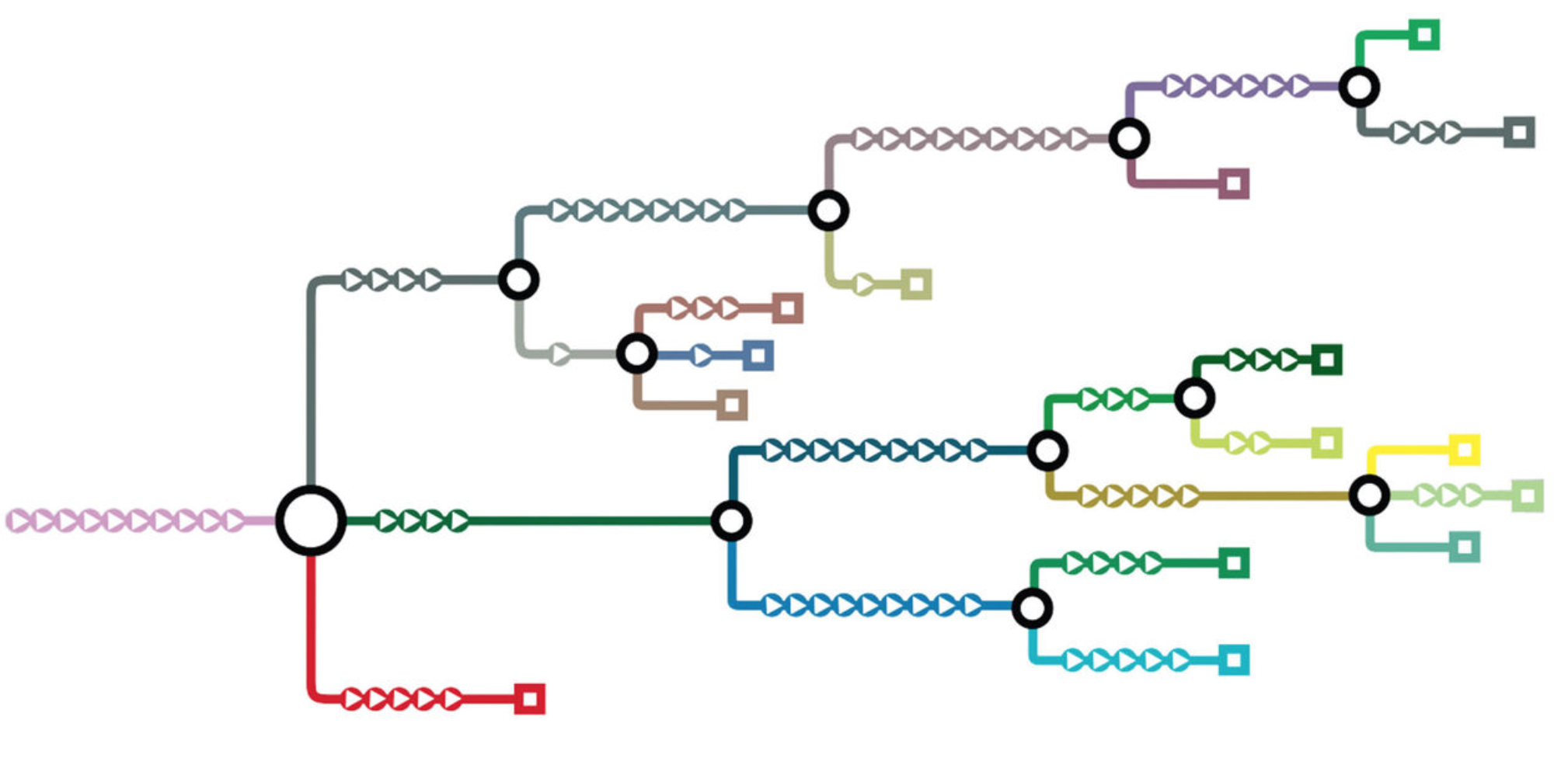

The False Dichotomy: We don’t live in a world that is either strictly global or national. It’s a false viewpoint to assume there can be only one or the other. Both co-exist and have done so for a very long time. Instead, it is a pendulum that swings back and forth over time and it often backtracks when we’ve gone too far in a particular direction. The direction of the swing is largely determined by politics and social sentiment. It is fair to say that things are swinging back to the nationalism (or more accurately, de-globalisation) side, as can be evidenced by Brexit, Trumpism and divergent national policies in tackling COVID-19. However, we can expect to see government interventions to secure supply chains and manufacturing returning to high-cost labour markets, facilitated by automation and increasingly protectionist policies. However, it won’t stop the culture of globalisation. Many of the things we regard as local actually have more global origins. For instance, the languages we speak and the number systems we use. Even tomatoes weren’t used in Italian food during the Roman Empire – they arrived much later from South America!

Change – it’s what happens after we were born: Often there is a fear response to change. But change, as I define it, is something that happened after you were born. Everything around us was new at some point, but it’s only scary if it arrived after you did. Whether this is food, language, work, industry, technology or social norms, the things we fear most are things we must learn about beyond childhood.

We’re all suffering from Future Shock. The future is arriving so fast that we are having trouble coping with it. A natural reaction is to hunker down, fight change, push back and develop a nationalist viewpoint to protect ourselves from the unknown. It’s a rational response for those who are hurt economically by the changes. Remember the word economics means ‘management of the home’. For example, if I lose my job to a factory that is moving to a low-cost labour market, it becomes very difficult for me to manage my home. To me, it matters little that my country’s GDP grew. While the narrative of change is often sold as positive by those pushing for it, it always has winners and losers. Even if we are the losers, the most constructive response is still adaptation – mainly because we don’t get to choose whether or not the world will change.

Relative Advantage: Globalisation itself is the natural evolution of basic trade. In its simplest form, it can be explained by the relative advantage different geographies have. Warm climate economies trade bananas for potatoes with cold climate economies. Now they both have bananas and potatoes – they are both better off through exchange. This is also true for commodity materials, expertise and production capacity. In recent decades, relative advantage has been usurped by a singular relative advantage – cost of production. It has become less about which country or region can or can’t do something and more about who does it cheaper. It’s true for industries at the bottom and the top of the technology stack. This is why we have oranges imported from Mexico being sold in Australian supermarkets. It’s not that we can’t grow them here – it’s that we can’t do it for the same price. It’s also why our car industry closed down. This is part of the reason we have a financialisation of developed economies.

Globalisation in Established vs Developing Economies: Given the shift toward low-cost labour as the driving force behind globalisation, it would appear that developing economies benefit more than developed economies from globalisation. As production shifts from high-cost to low-cost markets, a larger percentage of the developing economy’s population tends to benefit. In the high-cost markets, a smaller portion of the economy – largely the owners of capital – tend to win. In this instance, it is incumbent upon governments to ensure displaced workers find a place in the new economy. They must move their populace up the employment value chain as industries wind back. If this doesn’t happen, the net result tends to be increasing income inequality – a trend that has been well-documented over the past few decades.

Two Places at Once: Globalisation is at its best when it allows something to be in two places at once. This is the case with international cuisine, language, skills, expertise, products, machinery, procedures and techniques. When globalisation expands horizons, access and capability, we all benefit. Often though, it’s a zero sum game when jobs in industry X leave one place and go to another.

The Substitution Effect: If an industry can only be in one place, then we need to pay close attention to the substitution effect. Who will be the primary beneficiaries of the shift? Consumers, producers or both? Where will the former participants in industry X go? Will the benefits of something changing places be shared or hoarded by a fortunate few? Something becoming cheaper doesn’t make the economy better unless the new efficiency gain has a multiplier effect.

Co-operation or Competition: We need a stronger co-operative effort when it comes the global economy. The shift towards global competition has lead to increased nationalism and radical actions in home states. If people feel as though they have to compete in a rigged game, they often arrive with pitchforks. A global economy will need to have rules that all participants abide by if globalisation is ever to be the utopia economists claim it to be. The most important issues of our time don’t require competition, but instead co-operation. This is a hard thing to do when sovereign countries have competing objectives and incentives.

The Matching Principal: The most important thing we must consider when it comes to nationalism or globalisation is that we must match the issues. National problems need to be solved with national policies. Likewise global issues, like the climate crisis, require an international effort to succeed. Trying to solve issues with a mismatched geographic boundary are doomed to fail.

Closing Thoughts:

We are often told we can’t compete against other markets because we’re not efficient enough. This is not really true. What is true is that overseas countries have lower costs, because they don’t have to abide by the same rules. How can we expect a countries like the UK, USA, Germany or Australia to compete with lower-cost countries like India and China when we have higher wages, stringent occupational health and safety standards and environmental regulations that they do not? Of course we can’t compete.

We are all playing the same game. With different sets of rules.

It’s an unfair game. Always has been. While the game of capitalism needs winners and losers, it’s all important we know which rules each side is playing by. We need to remember that in any game, we must protect our own players, pay respect to the competition, and know that players change and join new teams all the time.

– – –

Keep Thinking,

Steve.